Education and Electricity in Zambia

The State of Education in Zambia

This article looks at the potential linkages between the provision of electricity in schools and improved outcomes for education and local economies.

In January 2022 a total of 409,441 pupils in Zambia progressed to start their secondary school education in Grade 8. At the same time only 140,338 pupils will start their senior secondary education in Grade 10 due to lack of places in senior secondary schools. This will translate to roughly two-thirds of children who complete primary school not being able to have a full secondary school education.

It is well established that education enables upward socioeconomic mobility and is a key to escaping poverty. One of the aims of the UN’s 4th Sustainable Development Goal is by 2030 to ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes. At the moment Zambia faces a huge challenge in meeting its education and skill needs.

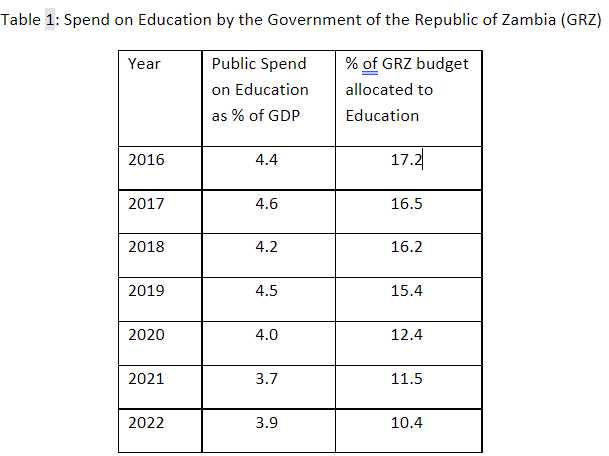

The UNESCO Education 2030 Framework for Action endorses two key benchmarks for public financing of education:

- Allocating at least 4–6 percent of GDP to education.

- Allocating at least 15–20 percent of public spending to education.

According to UNESCO, achieving the target for basic education by 2030 requires that countries spend at least the amounts listed above. The table below shows how the Zambian expenditure compares to these targets. It shows a decreasing trend of funds allocated to education with the last three years falling below the minimum recommended by the UN.

Additionally, it is worth noting that by international standards the absolute amount of government spending per pupil in Zambia is very low. The average amount spent per pupil across primary and secondary schools in Zambia in 2017 was $476 (purchasing power parity adjusted value). This is similar to the average for African countries but well below the average values of Latin America ($2000) and Asia ($2500 - $4000). Such low levels of spending could partly explain the poor quality of education outcomes in Zambian schools.

The quality of education outcomes in Zambia remains low. The OECD's Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) showed that in 2017 only 5% and 2% of sampled 15 year old pupils achieved the minimum level of proficiency in reading and mathematics respectively. This compared unfavourably to international OECD averages of pupils minimum level of performance of 80% in reading and 77% in mathematics.

It is acknowledged that there are many factors that contribute to the poor educational outcomes in Zambia, such as:

- Large class sizes;

- Lack of basic teaching aids like textbooks;

- Poor infrastructure;

- Difficult access to schools for learners due to long distances to travel;

- Low motivation among teachers caused by poor pay and conditions of service;

- Inadequate teacher training and insufficient numbers of teachers;

- Teaching not attracting the best and brightest candidates.

These issues are well known and need attention in tandem with those raised in this article.

Benefits of education to the individual and society are well documented. The rapidly changing, technology-driven and knowledge-based modern economies require the harnessing of human capital. Increased educational attainment accounts for about 50% of the economic growth in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries over the past 50 years. Quality education for all is a necessary requirement to achieve sustainable development and reduction of poverty.

Shortfalls in Electricity Access in Zambia

The aim of the 7th Sustainable Development Goal of the UN is to ensure access to affordable, reliable and sustainable energy for all by 2030. Currently the overall national electricity access rate at household level in Zambia is only 31%. Approximately 67% of the population in urban areas and only 4% in rural areas have access to electricity in their homes.

As part of the national strategy document, Vision 2030, GRZ has set electrification targets at 90% percent for urban and 51% percent for rural areas to be reached by 2030. The rural electrification target is based on the electrification of 1217 Rural Growth Centres (RGCs) through grid extensions, mini-hydro, and solar photo-voltaic (PV) installations as outlined in the Rural Electrification Master Plan (REMP) of 2008.

To achieve the rural electrification target of 51% by 2030 approximately $50 million per annum financing is required for the Rural Electrification Fund (REF). The REF receives finances from three sources:

- A 3% levy on ZESCO electricity bills to non-mining consumers

- National budget allocations

- Grants and loans from cooperating partners

The latest published accounts from ZESCO show no indication of the 3% levy charged to customers nor of any funds remitted to the Rural Electrification Authority. The Rural Electrification Authority website has no approved accounts to indicate its annual funding. The national budget allocations for rural electrification have averaged $15 million over the past seven years which is well below the $50 million required to achieve the stated rural electrification targets by 2030.

The National Energy Policy of 2019 has a stated objective to “achieve an optimal energy resources utilization to meet Zambia's domestic and non-domestic needs at the lowest total economic, financial, social, environmental and opportunity cost and establish Zambia as a net exporter of energy.” The outcomes and lessons learnt from the previous energy policy (2008) are not discussed. It is acknowledged that the implementation of the new National Energy Policy will require adequate financial resources but no plan is provided about where these funds will come from other than from the government coffers. This is a fundamental weakness of the policy and a replication of previous failed policies as shown in the charts above. More innovation is required.

The Cost of Universal Electricity Access

At the request of the Ministry of Energy and the Rural Electrification Authority the United States Agency for International Development Southern Africa Energy Program (USAID SAEP) has generated a geospatial model to determine the least-cost electrification solution for each household in Zambia. The model considers electricity demand, generation capacity and cost data to determine the least cost technology for each household. The four technologies considered are grid extension, solar mini-grid, hydro mini-grid and solar home systems.

The model shows that approximately $4 billion (non-discounted amount in 2017 real terms) would have been needed to achieve universal electricity access in Zambia by 2030. Solar home systems (SHS) would be the most affordable technologies for around 62% of households currently without electricity. Grid connections are deemed to be the most suitable solution for 34% of households without electricity. The remainder of un-electrified households (4%) would benefit from solar mini-grid solutions. The addition of productive agricultural activity such as milling and irrigation would increase the min-grid selection to 7% of the total and reduce solar home systems to 59%.

Why Solar PV Technology?

The cost of solar electricity has reduced dramatically in comparison to other technologies in recent years as shown in the diagram below. It is now the cheapest source of electricity for new power plants with a levelised cost of energy of $0.04/kWh. This has been due to the advances made in the entire production process of solar panel modules including increased R&D efforts creating greater efficiencies of the panels and increased economies of scales in manufacturing.

Zambia has an average solar irradiation of 5.5 kWh/m²/day with approximately 3,000 sunshine hours annually providing good potential for photovoltaic and solar thermal applications. At an irradiation conversion efficiency of 20%, solar panels would be able to generate 1.1 kWh/m2 of electricity per day. The AEP Zambia Geospatial Model assumes different electricity consumption levels for un-electrified rural and urban settlements as shown in the figure below.

The solar panel sizes required to fulfil the household electricity demand for each settlement type are as follows: New Paragraph

It is noted that due to their high energy consumption levels modern energy cooking solutions do not appear in the proposed electrification systems. The model assumes that a higher consumption and payment level (Tier 5) would be required to include cooking solutions. However, a study into developing a grid or solar PV battery-supported electric cooking concept called eCook has shown that the estimated cooking energy requirement for a 5 person household is a minimum of 1.9 kWh. This would increase by a factor of 4 the proposed energy required for rural settlements and double it for low income urban settlements.

As Zambia looks to diversifying its energy sources it makes sense to move into solar electricity generation because of its low carbon content and low price relative to the other technologies. The benefits of being able to generate solar energy local to the point of use remove the costs of creating a large distribution network with its accompanying energy losses.

Case Studies of Universal Electrification:

South Africa

In South Africa prior to 1990, less than a third of the population had access to electricity. By the end of the decade, that proportion had doubled. More than 5 million households received access to electricity between 1990 and 2007. In 2019 the population electricity access rate was 94%. South Africa had a unique set of historical circumstances with the end of apartheid in the early 1990s. It also did not suffer from problems typical of developing countries such as lack of access to capital, lack of skills and lack of supply infrastructure.

The development of electrification policies required the establishment of electrification as a public problem with the portrayal of existing institutional arrangements as inadequate in relation to national goals. A government White Paper noted that:

‘‘Government recognises that household access to adequate energy services for cooking, heating, lighting and communication is a basic need. Whilst these needs can be met by various fuel-appliance combinations, government recognises that without access to electricity, a clean, convenient and desirable fuel, human development potential is ultimately constrained’’.

The main lessons that may be drawn from the South African electrification experience are:

- The institutional and planning arrangements that the South African programme developed;

- The development of appropriate local cost-driven technical innovations and standards;

- The clear acknowledgement of the social function of electrification and its funding from the state (rather than through cross-subsidies);

- Lack of an integrated household energy policy which would tackle the continued use of biomass fuels for thermal purposes (cooking and heating) in low-income households despite the provision of free basic electricity;

South Korea

In the fifteen years between 1965 and 1979 the proportion of rural households in South Korea with access to electricity increased from 12% to 98%. This contributed to a significant increase in rural household income levels and improved the quality of life in villages substantially. Crucial to the success was an approach that balanced local control and participation with central government control.

It was recognised that without electrification rural farmers were unable to achieve the benefits of agricultural modernisation that included improvements in crop yield, cropping intensities, area farmed and productivity, as well as decreased labour and time costs. Electricity is also crucial in increasing the value added that farmers can derive from further processing of their produce and also for using information and communication technology (ICT) to obtain information on market conditions. A further indirect impact is the potential for electricity, through providing lighting and enabling for ICT-based informal and formal learning, to improve the education and skill-levels of rural workers, and consequently increase the presence and productivity of rural industry. Additionally, access to electricity can affect agricultural productivity through health benefits by reducing the impact of indoor air pollution from biomass energy sources.

The rural electrification programme helped average rural household income increase almost ten-fold from 1970 to 1979 and the quality of life in villages was consequently significantly improved.

Systems Thinking

A systems thinking approach of networks, mimicking the diversity and redundancy that occurs in nature, would help achieve a fairer distribution of resources. The differences in structure between a centralised system and one that is decentralised or distributed are shown in the figure below. A centralised system, like the current electricity grid in Zambia, has very few dominant centres of control with all the other nodes within the network feeding from this centre. Failure of the central node can cause failure of all the other nodes. This has been the case with the country-wide electricity deficit experienced in 2015 and 2019 following low water levels at the Kariba Dam power station. This has led to decreased economic growth and lower standards of living during these periods of extensive electricity load shedding.

A more distributed electricity network would have many sources of power generation and be more resilient to the effects of a single failure. The various linkages would also mean that there is less scope for a single failure in the distribution network to cause large network-wide failures. Distributed networks can also be created in a more modular fashion, with small sections developed at a time, leading to smaller capital cost requirements.

The advantages of distributed systems are as follows:

- Fault tolerant (resilient) – Many sources of control and network pathways that can be used when a single point fails.

- Scalable – Local systems can be created with little capital investment and joined up later to form a larger network as funds become available.

Disadvantages of distributed systems include:

- Higher maintenance costs – Require more skilled manpower to keep local networks working

- More difficult to deploy – Require greater planning and management skills to design and deploy

The systems thinking approach is developed further by Meadows. Complex systems both in nature and manmade evolve through innovations and deviations from the norm. Similarly experiments at the cutting edges can provide the transformation needed to create distributive and regenerative (sustainable) economies. Meadows argues that finding the leverage points in an economy can help achieve the necessary change for overall transformation. By making small changes at the right point, such as the provision of electricity to all schools, larger development changes can be achieved in the wider economic system.

Pay-As-You-Go

An innovative way of paying for off-grid solar systems has been developed by the Kenyan company M-Kopa. Their pay-as-you-go solar financing model allows instant access to products, while building ownership over time through flexible micro-payments. Customers pay a small upfront charge for their solar home kit. The balance is then paid off in instalments using a mobile money service. This has allowed low income families that previously used kerosene lamps for lighting to acquire electrical lighting, reduce indoor air pollution and save money. For pay-as-you-go methods to work on a large scale there needs to be appropriate financial and legislative support from the government to facilitate the start-up and growth of such businesses.

The Environmental and Human Cost of Not Changing Course

Zambia is one of the most forested countries in Africa with approximately 67% (49.5 million hectares) of its land surface covered by forests. Forests are a source of livelihood for people in rural areas providing a source of wood fuel, food, pasture and fodder, medicines and household utility items as well as regulating the water and carbon cycles. Forests also provide natural habitat for many species of animals and insects and help preserve soil structures.

Deforestation is a major problem in Zambia, with annual rates estimated at around 250,000 to 300,000 hectares. The role that the use of charcoal and firewood plays in deforestation is significant:

- 84% of rural households use firewood for cooking, with charcoal used by 13 percent of households.

- In urban areas the majority of households (59%) use charcoal for cooking with firewood use at 6 percent.

The high dependence on wood fuel is due to low electricity access, the high cost of efficient alternatives coupled with low incomes and inadequate enforcement of legislation and coordination among key sector institutions. Charcoal production is the biggest single driver of wood extraction and the primary cause of deforestation and forest degradation. Charcoal production contributes to the degradation of 190,000 hectares of forest annually.

If deforestation continues at the current rate and accelerates due to increasing population pressures, Zambia will experience severe losses of natural capital and socio-economic and environmental benefits. Additionally the country’s contribution towards the fight against climate change will be diminished. In monetary terms the annual deforestation rate results in an annual loss of $0.5 billion of natural capital stock. It therefore becomes imperative to establish a more sustainable source of energy for the bulk of the users of charcoal and wood fuels.

The use of solid fuels such as firewood and charcoal in cooking can cause household air pollution that results in respiratory illnesses, heart problems and death. Indoor air pollution causes more than 4 million premature deaths around the world every year with 50% being in children under the age of 5. Women in rural areas of Zambia are particularly affected due to the burden of collecting fuel and cooking that predominantly falls upon them. Innovative solutions for clean cooking are needed urgently to address the most basic needs of the poor while also delivering climate benefits.

Links Between Education and Electricity

A review of the links between education outcomes and the presence of electricity in schools is discussed in the article by Sovacool and Ryan. It shows that the lack of electricity in schools has persisted across the world despite growth in large-scale electricity networks.

It is shown that electrification of homes, schools and communities produces positive educational effects such as:

- Lighting for extended studying time leading to better quality and quantity of education

- Facilitation of greater information technology (IT) use including access to the internet which improves awareness of the wider world.

- Improved learning of technical and vocational subjects that require access to electricity.

- Enhanced staff retention due to better living and working conditions

- Better teacher training provided by availability of IT facilities.

- Better school performance due to reduced truancy and absenteeism, higher enrolment and completion rates and better examination scores.

- Wider community benefits such as improved sanitation and health, gender empowerment and reduced migration away from the region.

A number of challenges in providing electricity to all schools were identified as follows:

- Financing: The cost of connecting schools to the electricity grid or using off-grid systems is expensive. Building new power plants and extending the national grid is beyond the financial capability of many governments. When electricity access is provided to schools many may not afford to pay the running and maintenance costs. However, it is noted that the much needed electrification of schools is unlikely to happen without a deliberate and concerted effort to find the necessary funding.

- Technical problems: The lack of skilled manpower to operate and maintain new electricity equipment would be detrimental to its rollout. Inadequate infrastructure such as lack of suitable roads or adequate building structures would make it difficult to make the electrical connection possible. Theft and vandalism are also vices that may impede the successful use of any new electrical facilities.

- Lack of household access to electricity: Some evidence suggests that household electrification is more beneficial on education than school electrification. Electricity in the homes allows children to study for longer and teachers to prepare lessons outside school. A World Bank study showed that “rural electrification of households indirectly improves the propensity of a child to stay in school”. The benefits to households in rural areas is limited because electricity is predominantly used for lighting and communication purposes with little used for cooking and thus not immediately removing the health dangers of cooking using biomass fuels e.g. charcoal, and the accompanying environmental damage.

- Urban bias: There is a tendency by decision makers, who are largely urban based, to favour solutions for urban areas. Rural areas are less productive in terms of school learning outcomes and as a result suffer further neglect in policy decisions. It is important that a more distributive approach to resource allocation is taken by policy makers to reduce the inequality that rural areas suffer from.

- Other factors not related to energy access: This includes issues such as low quality teacher training, insufficient teacher numbers, poor building infrastructure and lack of textbooks. These may be considered more important than electricity provision but on their own are unlikely to provide the boost to learning outcomes that electrification provides.

There are 9733 primary and secondary schools in Zambia of which approximately 80% are in rural areas and do not have access to electricity. Increasing access to electricity in addition to other school infrastructure improvements and better teacher training are required for Zambia to attain the education outcomes required for sustainable development.

Page Break

Conclusions – Use Schools as Centres for Universal Electrification

Schools should be selected as the sites from which to achieve universal electrification using a mixture of grid connections, off-grid solar home systems and solar mini-grids. Electrifying all schools would provide a much needed boost to the quality of education provision and increase the development of local economies. This would act as a catalyst to connecting domestic dwellings to local electricity networks and then eventually to wider grid networks.

The benefits of universal electrification through schools are many and include the following:

- Reducing poverty and inequality through provision of better education for all and the creation of a skilled labour force with higher productivity levels;

- Sustainable growth of the economy due to increased use of solar renewable energy that facilitates the development of new technology-based industries and helps preserve the natural environment for future generations;

- Economic diversification of farming into high yield agriculture and agri-processing and creation of other export-oriented industries;

- Achieving energy self-sufficiency, security and resilience;

- Increased quality of life due to use of labour saving domestic appliances and industrial equipment.

The actions that would need to be taken to achieve universal electrification of schools are as follows:

- A concerted and deliberate effort by the government to create universal electricity and education access as a moral, social and economic imperative;

- Acceptance as a matter of public policy that the current levels of education and electricity access are problems that hinder development and require innovative solutions;

- Acknowledgement that the current plans identified in national development documents are inadequate to create the conditions for poverty reduction and sustainable economic growth;

- Increased government funding into education to levels that will provide universal access to quality education for all children up to grade 12 level by 2030;

- Development of a universal electricity access programme with solar PV technology at its heart;

- Establishment of financing mechanisms for low income people to acquire electricity such as pay-as-you-go, cross-subsidy from other electricity users or direct public investment methods. A distributed modular electricity system would allow for small-scale experimentation and innovation using relatively small amounts of capital funding;

- Technology acquisition through foreign direct investment followed by development of local industry, and research and development to design and manufacture home-grown solutions for solar panel technology and electrical cooking systems;

Page Break

References

- https://www.lusakatimes.com/2022/01/03/education-minister-announces-the-official-results-of-the-2021-grade-seven-and-grade-nine/

- https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/education/

- Education for All (EFA) Monitoring Report. Education for All 2000–2015: Achievements and Challenges. Paris: UNESCO. Available at: https://unesdoc. unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000232205.

- http://www.parliament.gov.zm/publications/budget-debates

- African Economic Outlook - Developing Africa’s Workforce for the Future – ADB

- https://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisa-for-development/Zambia_PISA_D_national_report.pdf

- National Energy Policy, 2019, GRZ

- Rural Electrification Master Plan For Zambia 2008 – 2030, GRZ, rea.org.zm/about-us/remp.html

- Electricity Service Access Project (P162760), The World Bank, 2017

- ZESCO Integrated Report 2017, https://www.zesco.co.zm/ourBusiness/financialStatement

- http://www.rea.org.zm/

- National Energy Policy, 2019, Republic of Zambia

- SAEP Zambia Geospatial Model, USAID, 2018

- Why did renewables become so cheap so fast? And what can we do to use this global opportunity for green growth?, Max Roser, December 01 2020, https://ourworldindata.org/cheap-renewables-growth

- National Energy Policy, 2019, Republic of Zambia

- eCook Zambia Prototyping Report – March 2019 Final Report , Leary, J., Serenje, N., Mwila F., Batchelor S., Leach M., Brown, E., Scott, N., Yamba, F., https://elstove.com/innovate-reports/

- South Africa's rapid electrification programme: Policy, institutional, planning, financing and technical innovations, Bernard Bekkera, Anton Eberhard and Andrew Marquard, Energy Policy, Volume 36, Issue 8, August 2008, Pages 3125-3137

- https://www.iea.org/reports/sdg7-data-and-projections/access-to-electricity

- Rural electrification and development in South Korea, Terry van Gevelt, Energy for Sustainable Development, Volume 23, December 2014, Pages 179-187, https://www-sciencedirect-com.libezproxy.open.ac.uk/science/article/pii/S097308261400091X

- https://berty.tech/blog/decentralized-distributed-centralized

- Thinking in Systems, Donella H. Meadows, Chelsea Green Publishing, 1993

- m-kopa.com

- https://www.pv-magazine.com/2019/10/19/the-weekend-read-a-bump-in-the-road-for-pay-as-you-go-solar-and-self-sustainability/

- National Investment Plan to Reduce Deforestation and Forest Degradation (2018-2022), Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources, Republic of Zambia, November 2017

- Zambia country profile Monitoring, reporting and verification for REDD+, Center for International Forestry Research, USAID, 2014

- Clean Cooking, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/partnership/?p=36652

- The geography of energy and education: Leaders, laggards, and lessons for achieving primary and secondary school electrification, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 58 (2016) 107-123

Ministry of General Education Website, https://www.moge.gov.zm (values for 2017) New Paragraph